Introduction to the Unix Shell

Questions |

Objectives |

|---|---|

|

|

About this tutorial

This tutorial was heavily adapted from the Shell Novice tutorial created by Software Carpentry. It has been shortened to fit our time frame.

Background

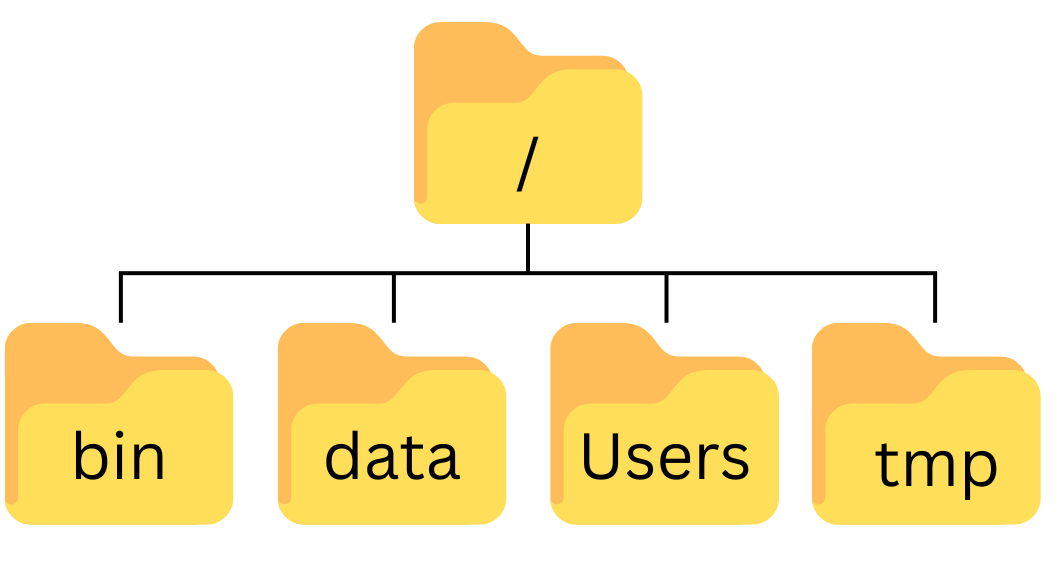

We interact with computers in many different ways, such as through a keyboard and mouse, and touch screen interfaces. The most widely used way to interact with personal computers is called a graphical user interface (GUI). With a GUI, we give instructions by clicking a mouse and using menu-driven interactions.

While the visual aid of a GUI makes it intuitive to use, this way of delivering instructions to a computer scales very poorly. Imagine the following task: you have to copy the third line of one thousand text files in one thousand different directories and paste it into a single file. Using a GUI, you would not only be clicking at your desk for several hours, but you could potentially also commit an error in the process of completing this repetitive task. This is where we take advantage of the Unix shell. The Unix shell is both a command-line interface (CLI) and a scripting language, allowing such repetitive tasks to be done automatically and fast. With the proper commands, the shell can repeat tasks with or without some modification as many times as we want. Using the shell, the task in the literature example can be accomplished in seconds.

The Shell

The shell is a program where users can type commands. With the shell, it’s possible to invoke complicated programs or simple commands with only one line of code. The most popular Unix shell is Bash (the Bourne Again SHell — so-called because it’s derived from a shell written by Stephen Bourne). Bash is the default shell on most implementations of Unix (Mac computers running macOS Catalina or later releases, the default Unix Shell is “Zsh”) and in most packages that provide Unix-like tools for Windows. Note that ‘Git Bash’ is a piece of software that enables Windows users to use a Bash-like interface when interacting with Git.

Using the shell will take some effort and some time to learn. While a GUI presents you with choices to select, CLI choices are not automatically presented to you, so you must learn a few commands like new vocabulary in a language you’re studying. Luckily, a small number of “words” (i.e. commands) gets you a long way, and we’ll cover those essential few today.

The grammar of a shell allows you to combine existing tools into powerful pipelines and handle large volumes of data automatically. Sequences of commands can be written into a script, improving the reproducibility of workflows.

In addition, the command line is often the easiest way to interact with remote machines and supercomputers. Familiarity with the shell is near essential to run a variety of specialized tools and resources including high-performance computing systems. As clusters and cloud computing systems become more popular for scientific data crunching, being able to interact with the shell is becoming a necessary skill. We can build on the command-line skills covered here to tackle a wide range of scientific questions and computational challenges.

Let’s get started.

The prompt

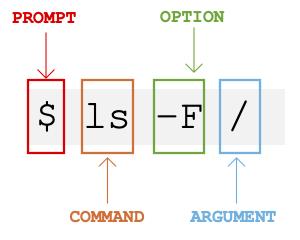

When the shell is first opened, you are presented with a prompt, indicating that the shell is waiting for input.

$The shell typically uses $ as the prompt, but may use a different symbol. In the examples for this lesson, we’ll show the prompt as $. Most importantly, do not type the prompt when typing commands. Only type the command that follows the prompt. This rule applies both in these lessons and in lessons from other sources. Also note that after you type a command, you have to press the Enter key to execute it.

The prompt is followed by a text cursor, a character that indicates the position where your typing will appear. The cursor is usually a flashing or solid block, but it can also be an underscore or a pipe. You may have seen it in a text editor program, for example.

Note that your prompt might look a little different. In particular, most popular shell environments by default put your user name and the host name before the $. Such a prompt might look like, e.g.:

sklucas@localhost $The prompt might even include more than this. Do not worry if your prompt is not just a short $. This lesson does not depend on this additional information and it should also not get in your way. The only important item to focus on is the $ character itself and we will see later why.

So let’s try our first command, ls, which is short for listing. This command will list the contents of the current directory:

$ lsDesktop Downloads Movies Pictures

Documents Library Music PublicA Typical Problem

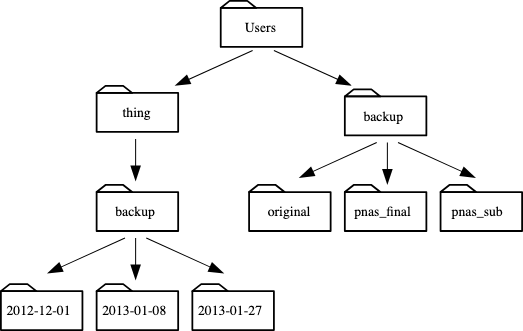

You are a marine biologist who has just returned from a six-month survey of the North Pacific Gyre, where you have sampled gelatinous marine life in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. You have 1520 samples that you’ve run through an assay machine to measure the relative abundance of 300 proteins. You need to run these 1520 files through an imaginary program called

goostats.sh. In addition to this huge task, you have to write up results by the end of the month, so your paper can appear in a special issue of Aquatic Goo Letters.If you choose to run

goostats.shby hand using a GUI, you’ll have to select and open a file 1520 times. Ifgoostats.shtakes 30 seconds to run each file, the whole process will take more than 12 hours. With the shell, you can instead assign your computer this mundane task while you focuses her attention on writing your paper.The next few lessons will explore the ways you can achieve this. More specifically, the lessons explain how you can use a command shell to run the

goostats.shprogram, using loops to automate the repetitive steps of entering file names, so that your computer can work while you write your paper.As a bonus, once you have put a processing pipeline together, you will be able to use it again whenever you collect more data.

In order to achieve your task, you need to know how to:

- navigate to a file/directory

- create a file/directory

- check the length of a file

- chain commands together

- retrieve a set of files

- iterate over files

- run a shell script containing your pipeline

Download files:

You need to download some files to follow this lesson.

Download shell-lesson-data.zip and move the file to your Desktop.

Unzip/extract the file. Let your instructor know if you need help with this step. You should end up with a new folder called

shell-lesson-dataon your Desktop.

- A shell is a program whose primary purpose is to read commands and run other programs.

- This lesson uses Bash, the default shell in many implementations of Unix.

- Programs can be run in Bash by entering commands at the command-line prompt.

- The shell’s main advantages are its high action-to-keystroke ratio, its support for automating repetitive tasks, and its capacity to access networked machines.

- A significant challenge when using the shell can be knowing what commands need to be run and how to run them.

Creating, moving, removing

| Questions | Objectives |

|---|---|

|

|

Creating Directories and Files

We now know how to explore files and directories, but how do we create them in the first place?

In this episode we will learn about creating and moving files and directories, using the exercise-data/writing directory as an example.

Step one: see where we are and what we already have

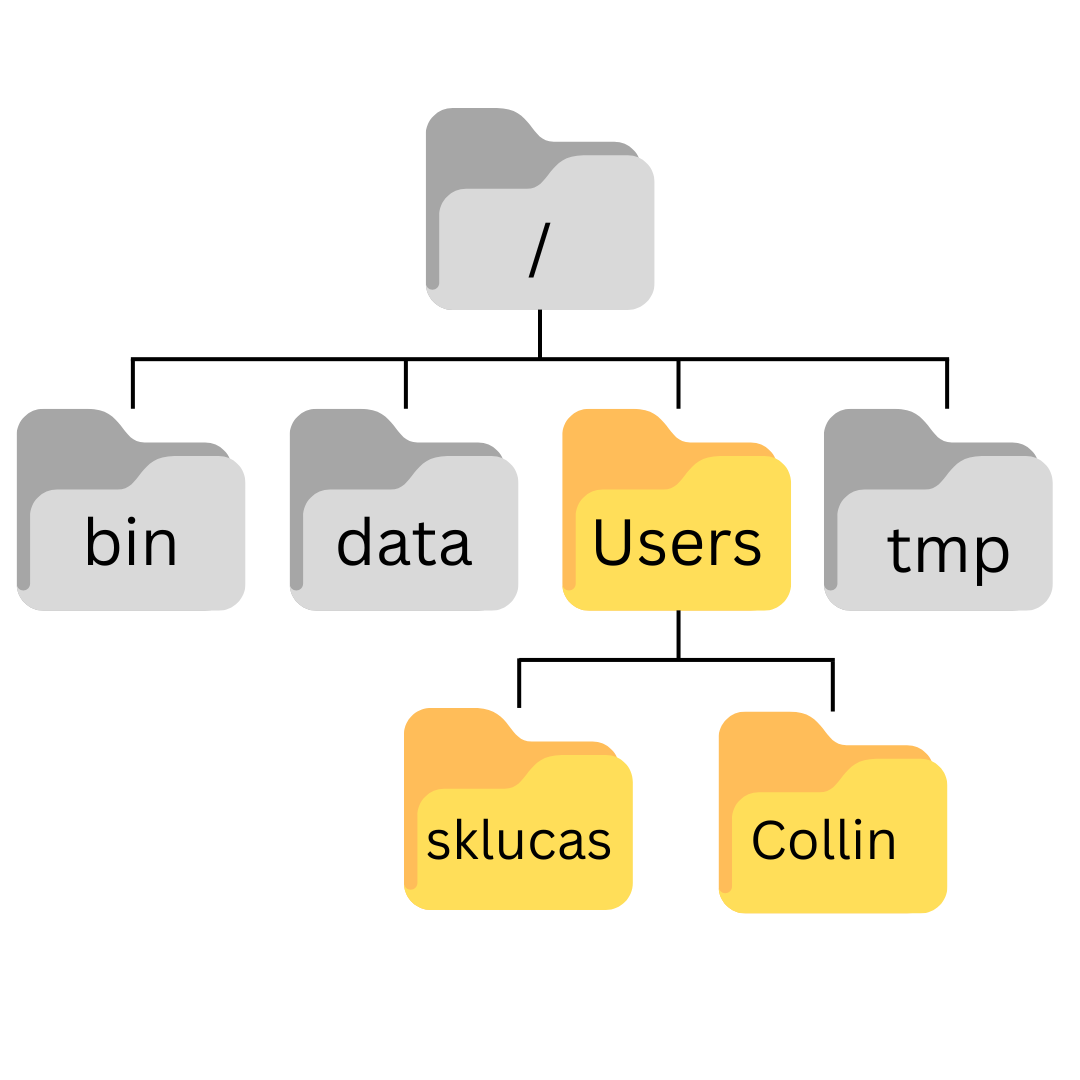

We should still be in the shell-lesson-data directory on the Desktop, which we can check using:

$ pwd/Users/sklucas/Desktop/shell-lesson-dataNext we’ll move to the exercise-data/writing directory and see what it contains:

$ cd exercise-data/writing/

$ ls -Fhaiku.txt LittleWomen.txtCreate a directory

Let’s create a new directory called thesis using the command mkdir thesis (which has no output):

$ mkdir thesisAs you might guess from its name, mkdir means ‘make directory’. Since thesis is a relative path (i.e., does not have a leading slash, like /what/ever/thesis), the new directory is created in the current working directory:

$ ls -Fhaiku.txt LittleWomen.txt thesis/Since we’ve just created the thesis directory, there’s nothing in it yet:

$ ls -F thesisNote that mkdir is not limited to creating single directories one at a time. The -p option allows mkdir to create a directory with nested subdirectories in a single operation:

$ mkdir -p ../project/data ../project/resultsThe -R option to the ls command will list all nested subdirectories within a directory. Let’s use ls -FR to recursively list the new directory hierarchy we just created in the project directory:

$ ls -FR ../project../project/:

data/ results/

../project/data:

../project/results:Create a text file

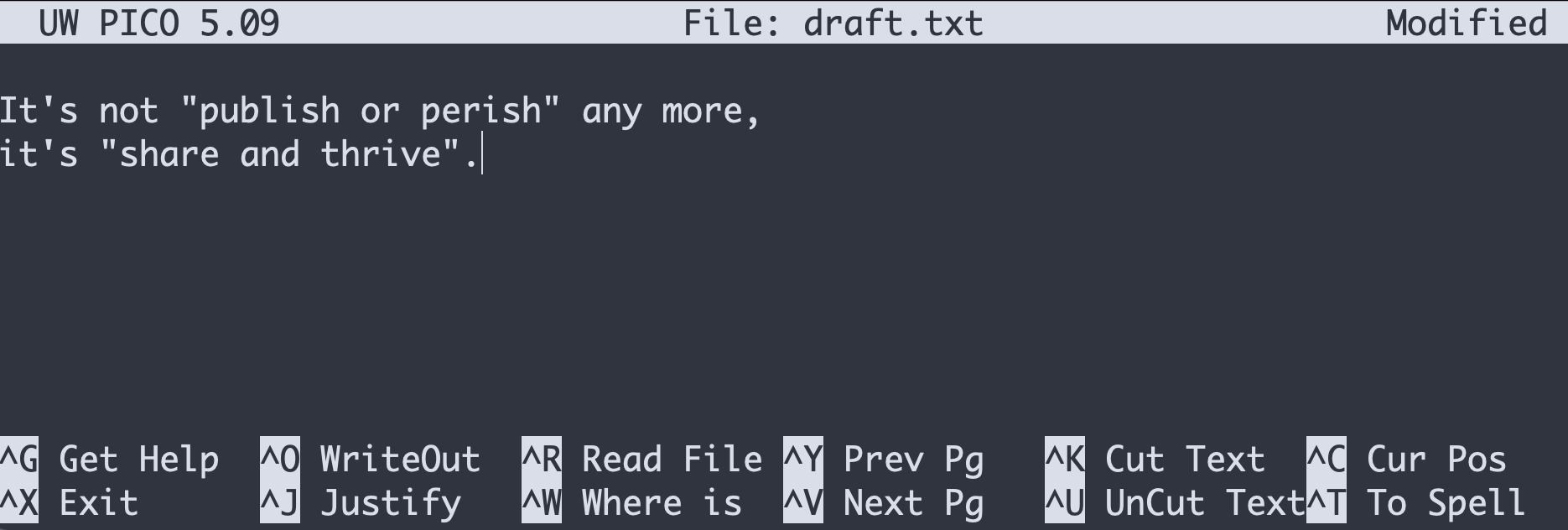

Let’s change our working directory to thesis using cd, then run a text editor called Nano to create a file called draft.txt:

$ cd thesis

$ nano draft.txtLet’s type a few lines of text:

Once we’re happy with our text, we can press Ctrl+O (press the Ctrl or Control key and, while holding it down, press the O key) to write our data to disk. We will be asked to provide a name for the file that will contain our text. Press Return to accept the suggested default of draft.txt.

Once our file is saved, we can use Ctrl+X to quit the editor and return to the shell.

nano doesn’t leave any output on the screen after it exits, but ls now shows that we have created a file called draft.txt:

$ lsdraft.txtWhat’s in a name?

You may have noticed that all of your files are named ‘something dot something’, and in this part of the lesson, we always used the extension

.txt. This is just a convention; we can call a filemythesisor almost anything else we want. However, most people use two-part names most of the time to help them (and their programs) tell different kinds of files apart. The second part of such a name is called the filename extension and indicates what type of data the file holds:.txtsignals a plain text file,.cfgis a configuration file full of parameters for some program or other,.pngis a PNG image, and so on.This is just a convention, albeit an important one. Files merely contain bytes; it’s up to us and our programs to interpret those bytes according to the rules for plain text files, PDF documents, configuration files, images, and so on.

Naming a PNG image of a whale as

whale.mp3doesn’t somehow magically turn it into a recording of whale song, though it might cause the operating system to associate the file with a music player program. In this case, if someone double-clickedwhale.mp3in a file explorer program, the music player will automatically (and erroneously) attempt to open thewhale.mp3file.

Moving Files and Directories

Returning to the shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/writing directory,

$ cd ~/Desktop/shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/writingIn our thesis directory we have a file draft.txt which isn’t a particularly informative name, so let’s change the file’s name using mv, which is short for ‘move’:

$ mv thesis/draft.txt thesis/quotes.txtThe first argument tells mv what we’re ‘moving’, while the second is where it’s to go. In this case, we’re moving thesis/draft.txt to thesis/quotes.txt, which has the same effect as renaming the file. Sure enough, ls shows us that thesis now contains one file called quotes.txt:

$ ls thesisquotes.txtOne must be careful when specifying the target file name, since mv will silently overwrite any existing file with the same name, which could lead to data loss. By default, mv will not ask for confirmation before overwriting files. However, an additional option, mv -i (or mv --interactive), will cause mv to request such confirmation.

Note that mv also works on directories.

Let’s move quotes.txt into the current working directory. We use mv once again, but this time we’ll use just the name of a directory as the second argument to tell mv that we want to keep the filename but put the file somewhere new. (This is why the command is called ‘move’.) In this case, the directory name we use is the special directory name . that we mentioned earlier.

$ mv thesis/quotes.txt .The effect is to move the file from the directory it was in to the current working directory. ls now shows us that thesis is empty:

$ ls thesis$Alternatively, we can confirm the file quotes.txt is no longer present in the thesis directory by explicitly trying to list it:

$ ls thesis/quotes.txtls: cannot access 'thesis/quotes.txt': No such file or directoryls with a filename or directory as an argument only lists the requested file or directory. If the file given as the argument doesn’t exist, the shell returns an error as we saw above. We can use this to see that quotes.txt is now present in our current directory:

$ ls quotes.txtquotes.txtCopying Files and Directories

The cp command works very much like mv, except it copies a file instead of moving it. We can check that it did the right thing using ls with two paths as arguments — like most Unix commands, ls can be given multiple paths at once:

$ cp quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txt

$ ls quotes.txt thesis/quotations.txtquotes.txt thesis/quotations.txtWe can also copy a directory and all its contents by using the recursive option -r, e.g. to back up a directory:

$ cp -r thesis thesis_backupWe can check the result by listing the contents of both the thesis and thesis_backup directory:

$ ls thesis thesis_backupthesis:

quotations.txt

thesis_backup:

quotations.txtIt is important to include the -r flag. If you want to copy a directory and you omit this option you will see a message that the directory has been omitted because -r not specified.

$ cp thesis thesis_backup

cp: -r not specified; omitting directory 'thesis'Removing files and directories

Returning to the shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/writing directory, let’s tidy up this directory by removing the quotes.txt file we created. The Unix command we’ll use for this is rm (short for ‘remove’):

$ rm quotes.txtWe can confirm the file has gone using ls:

$ ls quotes.txtls: cannot access 'quotes.txt': No such file or directoryThe Unix shell doesn’t have a trash bin that we can recover deleted files from (though most graphical interfaces to Unix do). Instead, when we delete files, they are unlinked from the file system so that their storage space on disk can be recycled. Tools for finding and recovering deleted files do exist, but there’s no guarantee they’ll work in any particular situation, since the computer may recycle the file’s disk space right away.

If we try to remove the thesis directory using rm thesis, we get an error message:

$ rm thesisrm: cannot remove 'thesis': Is a directoryThis happens because rm by default only works on files, not directories.

rm can remove a directory and all its contents if we use the recursive option -r, and it will do so without any confirmation prompts:

$ rm -r thesisGiven that there is no way to retrieve files deleted using the shell, rm -r should be used with great caution (you might consider adding the interactive option rm -r -i).

Operations with Multiple Filenames

Oftentimes one needs to copy or move several files at once. This can be done by providing a list of individual filenames, or specifying a naming pattern using wildcards. Wildcards are special characters that can be used to represent unknown characters or sets of characters when navigating the Unix file system.

Using Wildcards for Accessing Multiple Files at Once

* is a wildcard, which represents zero or more other characters. Let’s consider the shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/alkanes directory: *.pdb represents ethane.pdb, propane.pdb, and every file that ends with ‘.pdb’. On the other hand, p*.pdb only represents pentane.pdb and propane.pdb, because the ‘p’ at the front can only represent filenames that begin with the letter ‘p’.

? is also a wildcard, but it represents exactly one character. So ?ethane.pdb could represent methane.pdb whereas *ethane.pdb represents both ethane.pdb and methane.pdb.

Wildcards can be used in combination with each other. For example, ???ane.pdb indicates three characters followed by ane.pdb, giving cubane.pdb ethane.pdb octane.pdb.

When the shell sees a wildcard, it expands the wildcard to create a list of matching filenames before running the preceding command. As an exception, if a wildcard expression does not match any file, Bash will pass the expression as an argument to the command as it is. For example, typing ls *.pdf in the alkanes directory (which contains only files with names ending with .pdb) results in an error message that there is no file called *.pdf. However, generally commands like wc and ls see the lists of file names matching these expressions, but not the wildcards themselves. It is the shell, not the other programs, that expands the wildcards.

cp [old] [new]copies a file.mkdir [path]creates a new directory.mv [old] [new]moves (renames) a file or directory.rm [path]removes (deletes) a file.*matches zero or more characters in a filename, so*.txtmatches all files ending in.txt.?matches any single character in a filename, so?.txtmatchesa.txtbut notany.txt.- Use of the Control key may be described in many ways, including

Ctrl-X,Control-X, and^X. - The shell does not have a trash bin: once something is deleted, it’s really gone.

- Most files’ names are

something.extension. The extension isn’t required, and doesn’t guarantee anything, but is normally used to indicate the type of data in the file. - Depending on the type of work you do, you may need a more powerful text editor than Nano.

Pipes and Filters

Questions |

Objectives |

|

|

Now that we know a few basic commands, we can finally look at the shell’s most powerful feature: the ease with which it lets us combine existing programs in new ways. We’ll start with the directory shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/alkanes that contains six files describing some simple organic molecules. The .pdb extension indicates that these files are in Protein Data Bank format, a simple text format that specifies the type and position of each atom in the molecule.

$ lscubane.pdb methane.pdb pentane.pdb

ethane.pdb octane.pdb propane.pdbLet’s run an example command:

$ wc cubane.pdb20 156 1158 cubane.pdbwc is the ‘word count’ command: it counts the number of lines, words, and characters in files (returning the values in that order from left to right).

If we run the command wc *.pdb, the * in *.pdb matches zero or more characters, so the shell turns *.pdb into a list of all .pdb files in the current directory:

$ wc *.pdb 20 156 1158 cubane.pdb

12 84 622 ethane.pdb

9 57 422 methane.pdb

30 246 1828 octane.pdb

21 165 1226 pentane.pdb

15 111 825 propane.pdb

107 819 6081 totalNote that wc *.pdb also shows the total number of all lines in the last line of the output.

If we run wc -l instead of just wc, the output shows only the number of lines per file:

$ wc -l *.pdb 20 cubane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

9 methane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

107 totalThe -m and -w options can also be used with the wc command to show only the number of characters or the number of words, respectively.

Capturing output from commands

Output page by page with less

We’ll continue to use cat in this lesson, for convenience and consistency, but it has the disadvantage that it always dumps the whole file onto your screen. More useful in practice is the command less (e.g. less lengths.txt). This displays a screenful of the file, and then stops. You can go forward one screenful by pressing the spacebar, or back one by pressing b. Press q to quit.

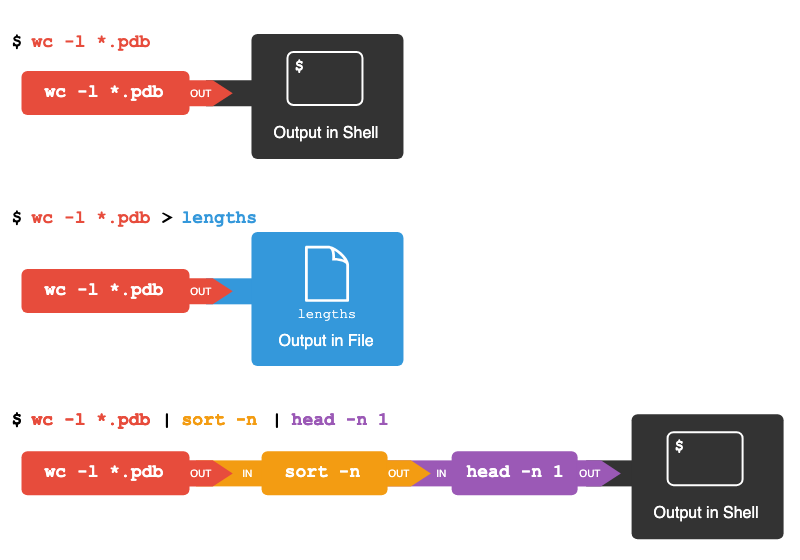

Which of these files contains the fewest lines? It’s an easy question to answer when there are only six files, but what if there were 6000? Our first step toward a solution is to run the command:

$ wc -l *.pdb > lengths.txtThe greater than symbol, >, tells the shell to redirect the command’s output to a file instead of printing it to the screen. This command prints no screen output, because everything that wc would have printed has gone into the file lengths.txt instead. If the file doesn’t exist prior to issuing the command, the shell will create the file. If the file exists already, it will be silently overwritten, which may lead to data loss. Thus, redirect commands require caution.

ls lengths.txt confirms that the file exists:

$ ls lengths.txtlengths.txtWe can now send the content of lengths.txt to the screen using cat lengths.txt. The cat command gets its name from ‘concatenate’ i.e. join together, and it prints the contents of files one after another. There’s only one file in this case, so cat just shows us what it contains:

$ cat lengths.txt 20 cubane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

9 methane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

107 totalFiltering output

Next we’ll use the sort command to sort the contents of the lengths.txt file. But first we’ll do an exercise to learn a little about the sort command:

We will also use the -n option to specify that the sort is numerical instead of alphanumerical. This does not change the file; instead, it sends the sorted result to the screen:

$ sort -n lengths.txt 9 methane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

20 cubane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

107 totalWe can put the sorted list of lines in another temporary file called sorted-lengths.txt by putting > sorted-lengths.txt after the command, just as we used > lengths.txt to put the output of wc into lengths.txt. Once we’ve done that, we can run another command called head to get the first few lines in sorted-lengths.txt:

$ sort -n lengths.txt > sorted-lengths.txt

$ head -n 1 sorted-lengths.txt 9 methane.pdbUsing -n 1 with head tells it that we only want the first line of the file; -n 20 would get the first 20, and so on. Since sorted-lengths.txt contains the lengths of our files ordered from least to greatest, the output of head must be the file with the fewest lines.

It’s a very bad idea to try redirecting the output of a command that operates on a file to the same file. For example:

$ sort -n lengths.txt > lengths.txtDoing something like this may give you incorrect results and/or delete the contents of lengths.txt.

Passing output to another command

In our example of finding the file with the fewest lines, we are using two intermediate files lengths.txt and sorted-lengths.txt to store output. This is a confusing way to work because even once you understand what wc, sort, and head do, those intermediate files make it hard to follow what’s going on. We can make it easier to understand by running sort and head together:

$ sort -n lengths.txt | head -n 1 9 methane.pdbThe vertical bar, |, between the two commands is called a pipe. It tells the shell that we want to use the output of the command on the left as the input to the command on the right.

This has removed the need for the sorted-lengths.txt file.

Combining multiple commands

Nothing prevents us from chaining pipes consecutively. We can for example send the output of wc directly to sort, and then send the resulting output to head. This removes the need for any intermediate files.

We’ll start by using a pipe to send the output of wc to sort:

$ wc -l *.pdb | sort -n 9 methane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

20 cubane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

107 totalWe can then send that output through another pipe, to head, so that the full pipeline becomes:

$ wc -l *.pdb | sort -n | head -n 1 9 methane.pdbThis is exactly like a mathematician nesting functions like log(3x) and saying ‘the log of three times x’. In our case, the algorithm is ‘head of sort of line count of *.pdb’.

The redirection and pipes used in the last few commands are illustrated below:

Tools designed to work together

This idea of linking programs together is why Unix has been so successful. Instead of creating enormous programs that try to do many different things, Unix programmers focus on creating lots of simple tools that each do one job well, and that work well with each other. This programming model is called ‘pipes and filters’. We’ve already seen pipes; a filter is a program like wc or sort that transforms a stream of input into a stream of output. Almost all of the standard Unix tools can work this way. Unless told to do otherwise, they read from standard input, do something with what they’ve read, and write to standard output.

The key is that any program that reads lines of text from standard input and writes lines of text to standard output can be combined with every other program that behaves this way as well. You can and should write your programs this way so that you and other people can put those programs into pipes to multiply their power.

Your Pipeline: Checking Files

You have run your samples through the assay machines and created 17 files in the north-pacific-gyre directory described earlier. As a quick check, starting from the shell-lesson-data directory, you type:

$ cd north-pacific-gyre

$ wc -l *.txtThe output is 18 lines that look like this:

300 NENE01729A.txt

300 NENE01729B.txt

300 NENE01736A.txt

300 NENE01751A.txt

300 NENE01751B.txt

300 NENE01812A.txt

... ...Now you type this:

$ wc -l *.txt | sort -n | head -n 5 240 NENE02018B.txt

300 NENE01729A.txt

300 NENE01729B.txt

300 NENE01736A.txt

300 NENE01751A.txtWhoops: one of the files is 60 lines shorter than the others. When you go back and check it, you see that you did that assay at 8:00 on a Monday morning — someone was probably in using the machine on the weekend, and you forgot to reset it. Before re-running that sample, you check to see if any files have too much data:

$ wc -l *.txt | sort -n | tail -n 5 300 NENE02040B.txt

300 NENE02040Z.txt

300 NENE02043A.txt

300 NENE02043B.txt

5040 totalThose numbers look good — but what’s that ‘Z’ doing there in the third-to-last line? All of your samples should be marked ‘A’ or ‘B’; by convention, your lab uses ‘Z’ to indicate samples with missing information. To find others like it, you do this:

$ ls *Z.txtNENE01971Z.txt NENE02040Z.txtSure enough, when you check the log on your laptop, there’s no depth recorded for either of those samples. Since it’s too late to get the information any other way, you must exclude those two files from your analysis. You could delete them using rm, but there are actually some analyses you might do later where depth doesn’t matter, so instead, you’ll have to be careful later on to select files using the wildcard expressions NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt.

wccounts lines, words, and characters in its inputs.catdisplays the contents of its inputs.sortsorts its inputs.headdisplays the first 10 lines of its input by default without additional arguments.taildisplays the last 10 lines of its input by default without additional arguments.command > [file]redirects a command’s output to a file (overwriting any existing content).command >> [file]appends a command’s output to a file.[first] | [second]is a pipeline: the output of the first command is used as the input to the second.- The best way to use the shell is to use pipes to combine simple single-purpose programs (filters).’ll have to be careful later on to select files using the wildcard expressions

NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt.

Repeating commands using loops

Loops are a programming construct which allow us to repeat a command or set of commands for each item in a list. As such they are key to productivity improvements through automation. Similar to wildcards and tab completion, using loops also reduces the amount of typing required (and hence reduces the number of typing mistakes).

Suppose we have several hundred genome data files named basilisk.dat, minotaur.dat, and unicorn.dat. For this example, we’ll use the exercise-data/creatures directory which only has three example files, but the principles can be applied to many many more files at once.

The structure of these files is the same: the common name, classification, and updated date are presented on the first three lines, with DNA sequences on the following lines. Let’s look at the files:

$ head -n 5 basilisk.dat minotaur.dat unicorn.datWe would like to print out the classification for each species, which is given on the second line of each file. For each file, we would need to execute the command head -n 2 and pipe this to tail -n 1. We’ll use a loop to solve this problem, but first let’s look at the general form of a loop, using the pseudo-code below:

# The word "for" indicates the start of a "For-loop" command

for thing in list_of_things

#The word "do" indicates the start of job execution list

do

# Indentation within the loop is not required, but aids legibility

operation_using/command $thing

# The word "done" indicates the end of a loop

done and we can apply this to our example like this:

$ for filename in basilisk.dat minotaur.dat unicorn.dat

> do

> echo $filename

> head -n 2 $filename | tail -n 1

> donebasilisk.dat

CLASSIFICATION: basiliscus vulgaris

minotaur.dat

CLASSIFICATION: bos hominus

unicorn.dat

CLASSIFICATION: equus monocerosThe shell prompt changes from $ to > and back again as we were typing in our loop. The second prompt, >, is different to remind us that we haven’t finished typing a complete command yet. A semicolon, ;, can be used to separate two commands written on a single line.

When the shell sees the keyword for, it knows to repeat a command (or group of commands) once for each item in a list. Each time the loop runs (called an iteration), an item in the list is assigned in sequence to the variable, and the commands inside the loop are executed, before moving on to the next item in the list. Inside the loop, we call for the variable’s value by putting $ in front of it. The $ tells the shell interpreter to treat the variable as a variable name and substitute its value in its place, rather than treat it as text or an external command.

In this example, the list is three filenames: basilisk.dat, minotaur.dat, and unicorn.dat. Each time the loop iterates, we first use echo to print the value that the variable $filename currently holds. This is not necessary for the result, but beneficial for us here to have an easier time to follow along. Next, we will run the head command on the file currently referred to by $filename. The first time through the loop, $filename is basilisk.dat. The interpreter runs the command head on basilisk.dat and pipes the first two lines to the tail command, which then prints the second line of basilisk.dat. For the second iteration, $filename becomes minotaur.dat. This time, the shell runs head on minotaur.dat and pipes the first two lines to the tail command, which then prints the second line of minotaur.dat. For the third iteration, $filename becomes unicorn.dat, so the shell runs the head command on that file, and tail on the output of that. Since the list was only three items, the shell exits the for loop.

Here we see > being used as a shell prompt, whereas > is also used to redirect output. Similarly, $ is used as a shell prompt, but, as we saw earlier, it is also used to ask the shell to get the value of a variable.

If the shell prints > or $ then it expects you to type something, and the symbol is a prompt.

If you type > or $ yourself, it is an instruction from you that the shell should redirect output or get the value of a variable.

When using variables it is also possible to put the names into curly braces to clearly delimit the variable name: $filename is equivalent to ${filename}, but is different from ${file}name. You may find this notation in other people’s programs.

We have called the variable in this loop filename in order to make its purpose clearer to human readers. The shell itself doesn’t care what the variable is called; if we wrote this loop as:

$ for x in basilisk.dat minotaur.dat unicorn.dat

> do

> head -n 2 $x | tail -n 1

> doneor:

$ for temperature in basilisk.dat minotaur.dat unicorn.dat

> do

> head -n 2 $temperature | tail -n 1

> doneit would work exactly the same way. Don’t do this. Programs are only useful if people can understand them, so meaningless names (like x) or misleading names (like temperature) increase the odds that the program won’t do what its readers think it does.

In the above examples, the variables (thing, filename, x and temperature) could have been given any other name, as long as it is meaningful to both the person writing the code and the person reading it.

Note also that loops can be used for other things than filenames, like a list of numbers or a subset of data.

Let’s continue with our example in the shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/creatures directory. Here’s a slightly more complicated loop:

$ for filename in *.dat

> do

> echo $filename

> head -n 100 $filename | tail -n 20

> doneThe shell starts by expanding *.dat to create the list of files it will process. The loop body then executes two commands for each of those files. The first command, echo, prints its command-line arguments to standard output. For example:

$ echo hello thereprints:

hello thereIn this case, since the shell expands $filename to be the name of a file, echo $filename prints the name of the file. Note that we can’t write this as:

$ for filename in *.dat

> do

> $filename

> head -n 100 $filename | tail -n 20

> donebecause then the first time through the loop, when $filename expanded to basilisk.dat, the shell would try to run basilisk.dat as a program. Finally, the head and tail combination selects lines 81-100 from whatever file is being processed (assuming the file has at least 100 lines).

We would like to modify each of the files in shell-lesson-data/exercise-data/creatures, but also save a version of the original files. We want to copy the original files to new files named original-basilisk.dat and original-unicorn.dat, for example. We can’t use:

$ cp *.dat original-*.datbecause that would expand to:

$ cp basilisk.dat minotaur.dat unicorn.dat original-*.datThis wouldn’t back up our files, instead we get an error:

cp: target `original-*.dat' is not a directoryThis problem arises when cp receives more than two inputs. When this happens, it expects the last input to be a directory where it can copy all the files it was passed. Since there is no directory named original-*.dat in the creatures directory, we get an error.

Instead, we can use a loop:

$ for filename in *.dat

> do

> cp $filename original-$filename

> doneThis loop runs the cp command once for each filename. The first time, when $filename expands to basilisk.dat, the shell executes:

cp basilisk.dat original-basilisk.datThe second time, the command is:

cp minotaur.dat original-minotaur.datThe third and last time, the command is:

cp unicorn.dat original-unicorn.datSince the cp command does not normally produce any output, it’s hard to check that the loop is working correctly. However, we learned earlier how to print strings using echo, and we can modify the loop to use echo to print our commands without actually executing them. As such we can check what commands would be run in the unmodified loop.

The following diagram shows what happens when the modified loop is executed and demonstrates how the judicious use of echo is a good debugging technique.

Your pipeline: Processing files

You are now ready to process your data files using goostats.sh — a shell script written by your supervisor. This calculates some statistics from a protein sample file and takes two arguments:

an input file (containing the raw data)

an output file (to store the calculated statistics)

Since you are still learning how to use the shell, you decides to build up the required commands in stages. Your first step is to make sure that you can select the right input files — remember, these are ones whose names end in ‘A’ or ‘B’, rather than ‘Z’. Moving to the north-pacific-gyre directory, you type:

$ cd

$ cd Desktop/shell-lesson-data/north-pacific-gyre

$ for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt

> do

> echo $datafile

> doneNENE01729A.txt

NENE01736A.txt

NENE01751A.txt

...

NENE02040B.txt

NENE02043B.txtYour next step is to decide what to call the files that the goostats.sh analysis program will create. Prefixing each input file’s name with ‘stats’ seems simple, so you modify your loop to do that:

$ for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt

> do

> echo $datafile stats-$datafile

> doneNENE01729A.txt stats-NENE01729A.txt

NENE01736A.txt stats-NENE01729A.txt

NENE01751A.txt stats-NENE01729A.txt

...

NENE02040B.txt stats-NENE02040B.txt

NENE02043B.txt stats-NENE02043B.txtYou haven’t actually run goostats.sh yet, but now you’re sure you can select the right files and generate the right output filenames.

Typing in commands over and over again is becoming tedious, though, and you are worried about making mistakes, so instead of re-entering your loop, you press ↑. In response, the shell re-displays the whole loop on one line (using semi-colons to separate the pieces):

$ for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do echo $datafile stats-$datafile; doneUsing the ←, you navigate to the echo command and change it to bash goostats.sh:

$ for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do bash goostats.sh $datafile stats-$datafile; doneWhen you press Enter, the shell runs the modified command. However, nothing appears to happen — there is no output. After a moment, you realize that since your script doesn’t print anything to the screen any longer, you has no idea whether it is running, much less how quickly. You kill the running command by typing Ctrl+C, uses ↑ to repeat the command, and edit it to read:

$ for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do echo $datafile;

bash goostats.sh $datafile stats-$datafile; doneWe can move to the beginning of a line in the shell by typing Ctrl+A and to the end using Ctrl+E.

When you run your program now, it produces one line of output every five seconds or so:

NENE01729A.txt

NENE01736A.txt

NENE01751A.txt

...1518 times 5 seconds, divided by 60, tells her that her script will take about two hours to run. As a final check, you open another terminal window, go into north-pacific-gyre, and uses cat stats-NENE01729B.txt to examine one of the output files. It looks good, so you decides to get some coffee and catch up on your reading.

Another way to repeat previous work is to use the history command to get a list of the last few hundred commands that have been executed, and then to use !123 (where ‘123’ is replaced by the command number) to repeat one of those commands. For example, if you types this:

$ history | tail -n 5456 for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do echo $datafile stats-$datafile; done

457 for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do echo $datafile stats-$datafile; done

458 for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do bash goostats.sh $datafile stats-$datafile; done

459 for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt; do echo $datafile; bash goostats.sh $datafile

stats-$datafile; done

460 history | tail -n 5then you can re-run goostats.sh on the files simply by typing !459.

There are a number of other shortcut commands for getting at the history.

Ctrl+R enters a history search mode ‘reverse-i-search’ and finds the most recent command in your history that matches the text you enter next. Press Ctrl+R one or more additional times to search for earlier matches. You can then use the left and right arrow keys to choose that line and edit it then hit Return to run the command.

!!retrieves the immediately preceding command (you may or may not find this more convenient than using ↑)!$retrieves the last word of the last command. That’s useful more often than you might expect: afterbash goostats.sh NENE01729B.txt stats-NENE01729B.txt, you can typeless !$to look at the filestats-NENE01729B.txt, which is quicker than doing ↑ and editing the command-line.

A

forloop repeats commands once for every thing in a list.Every

forloop needs a variable to refer to the thing it is currently operating on.Use

$nameto expand a variable (i.e., get its value).${name}can also be used.Do not use spaces, quotes, or wildcard characters such as ‘*’ or ‘?’ in filenames, as it complicates variable expansion.

Give files consistent names that are easy to match with wildcard patterns to make it easy to select them for looping.

Use the up-arrow key to scroll up through previous commands to edit and repeat them.

Use Ctrl+R to search through the previously entered commands.

Use

historyto display recent commands, and![number]to repeat a command by number.

Shell Scripts

We are finally ready to see what makes the shell such a powerful programming environment. We are going to take the commands we repeat frequently and save them in files so that we can re-run all those operations again later by typing a single command. For historical reasons, a bunch of commands saved in a file is usually called a shell script, but make no mistake — these are actually small programs.

Not only will writing shell scripts make your work faster, but also you won’t have to retype the same commands over and over again. It will also make it more accurate (fewer chances for typos) and more reproducible. If you come back to your work later (or if someone else finds your work and wants to build on it), you will be able to reproduce the same results simply by running your script, rather than having to remember or retype a long list of commands.

Let’s start by going back to alkanes/ and creating a new file, middle.sh which will become our shell script:

$ cd alkanes

$ nano middle.shThe command nano middle.sh opens the file middle.sh within the text editor ‘nano’ (which runs within the shell). If the file does not exist, it will be created. We can use the text editor to directly edit the file by inserting the following line:

head -n 15 octane.pdb | tail -n 5This is a variation on the pipe we constructed earlier, which selects lines 11-15 of the file octane.pdb. Remember, we are not running it as a command just yet; we are only incorporating the commands in a file.

Then we save the file (Ctrl-O in nano) and exit the text editor (Ctrl-X in nano). Check that the directory alkanes now contains a file called middle.sh.

Once we have saved the file, we can ask the shell to execute the commands it contains. Our shell is called bash, so we run the following command:

$ bash middle.shATOM 9 H 1 -4.502 0.681 0.785 1.00 0.00

ATOM 10 H 1 -5.254 -0.243 -0.537 1.00 0.00

ATOM 11 H 1 -4.357 1.252 -0.895 1.00 0.00

ATOM 12 H 1 -3.009 -0.741 -1.467 1.00 0.00

ATOM 13 H 1 -3.172 -1.337 0.206 1.00 0.00Sure enough, our script’s output is exactly what we would get if we ran that pipeline directly.

What if we want to select lines from an arbitrary file? We could edit middle.sh each time to change the filename, but that would probably take longer than typing the command out again in the shell and executing it with a new file name. Instead, let’s edit middle.sh and make it more versatile:

$ nano middle.shNow, within “nano”, replace the text octane.pdb with the special variable called $1:

head -n 15 "$1" | tail -n 5Inside a shell script, $1 means ‘the first filename (or other argument) on the command line’. We can now run our script like this:

$ bash middle.sh octane.pdbATOM 9 H 1 -4.502 0.681 0.785 1.00 0.00

ATOM 10 H 1 -5.254 -0.243 -0.537 1.00 0.00

ATOM 11 H 1 -4.357 1.252 -0.895 1.00 0.00

ATOM 12 H 1 -3.009 -0.741 -1.467 1.00 0.00

ATOM 13 H 1 -3.172 -1.337 0.206 1.00 0.00or on a different file like this:

$ bash middle.sh pentane.pdbATOM 9 H 1 1.324 0.350 -1.332 1.00 0.00

ATOM 10 H 1 1.271 1.378 0.122 1.00 0.00

ATOM 11 H 1 -0.074 -0.384 1.288 1.00 0.00

ATOM 12 H 1 -0.048 -1.362 -0.205 1.00 0.00

ATOM 13 H 1 -1.183 0.500 -1.412 1.00 0.00For the same reason that we put the loop variable inside double-quotes, in case the filename happens to contain any spaces, we surround $1 with double-quotes.

Currently, we need to edit middle.sh each time we want to adjust the range of lines that is returned. Let’s fix that by configuring our script to instead use three command-line arguments. After the first command-line argument ($1), each additional argument that we provide will be accessible via the special variables $1, $2, $3, which refer to the first, second, third command-line arguments, respectively.

Knowing this, we can use additional arguments to define the range of lines to be passed to head and tail respectively:

$ nano middle.shhead -n "$2" "$1" | tail -n "$3"We can now run:

$ bash middle.sh pentane.pdb 15 5ATOM 9 H 1 1.324 0.350 -1.332 1.00 0.00

ATOM 10 H 1 1.271 1.378 0.122 1.00 0.00

ATOM 11 H 1 -0.074 -0.384 1.288 1.00 0.00

ATOM 12 H 1 -0.048 -1.362 -0.205 1.00 0.00

ATOM 13 H 1 -1.183 0.500 -1.412 1.00 0.00By changing the arguments to our command, we can change our script’s behaviour:

$ bash middle.sh pentane.pdb 20 5ATOM 14 H 1 -1.259 1.420 0.112 1.00 0.00

ATOM 15 H 1 -2.608 -0.407 1.130 1.00 0.00

ATOM 16 H 1 -2.540 -1.303 -0.404 1.00 0.00

ATOM 17 H 1 -3.393 0.254 -0.321 1.00 0.00

TER 18 1This works, but it may take the next person who reads middle.sh a moment to figure out what it does. We can improve our script by adding some comments at the top:

$ nano middle.sh# Select lines from the middle of a file.

# Usage: bash middle.sh filename end_line num_lines

head -n "$2" "$1" | tail -n "$3"A comment starts with a # character and runs to the end of the line. The computer ignores comments, but they’re invaluable for helping people (including your future self) understand and use scripts. The only caveat is that each time you modify the script, you should check that the comment is still accurate. An explanation that sends the reader in the wrong direction is worse than none at all.

What if we want to process many files in a single pipeline? For example, if we want to sort our .pdb files by length, we would type:

$ wc -l *.pdb | sort -nbecause wc -l lists the number of lines in the files (recall that wc stands for ‘word count’, adding the -l option means ‘count lines’ instead) and sort -n sorts things numerically. We could put this in a file, but then it would only ever sort a list of .pdb files in the current directory. If we want to be able to get a sorted list of other kinds of files, we need a way to get all those names into the script. We can’t use $1, $2, and so on because we don’t know how many files there are. Instead, we use the special variable $@, which means, ‘All of the command-line arguments to the shell script’. We also should put $@ inside double-quotes to handle the case of arguments containing spaces ("$@" is special syntax and is equivalent to "$1" "$2" …).

Here’s an example:

$ nano sorted.sh# Sort files by their length.

# Usage: bash sorted.sh one_or_more_filenames

wc -l "$@" | sort -n$ bash sorted.sh *.pdb ../creatures/*.dat9 methane.pdb

12 ethane.pdb

15 propane.pdb

20 cubane.pdb

21 pentane.pdb

30 octane.pdb

163 ../creatures/basilisk.dat

163 ../creatures/minotaur.dat

163 ../creatures/unicorn.dat

596 totalSuppose we have just run a series of commands that did something useful — for example, creating a graph we’d like to use in a paper. We’d like to be able to re-create the graph later if we need to, so we want to save the commands in a file. Instead of typing them in again (and potentially getting them wrong) we can do this:

$ history | tail -n 5 > redo-figure-3.shThe file redo-figure-3.sh now contains:

297 bash goostats.sh NENE01729B.txt stats-NENE01729B.txt

298 bash goodiff.sh stats-NENE01729B.txt /data/validated/01729.txt > 01729-differences.txt

299 cut -d ',' -f 2-3 01729-differences.txt > 01729-time-series.txt

300 ygraph --format scatter --color bw --borders none 01729-time-series.txt figure-3.png

301 history | tail -n 5 > redo-figure-3.shAfter a moment’s work in an editor to remove the serial numbers on the commands, and to remove the final line where we called the history command, we have a completely accurate record of how we created that figure.

In practice, most people develop shell scripts by running commands at the shell prompt a few times to make sure they’re doing the right thing, then saving them in a file for re-use. This style of work allows people to recycle what they discover about their data and their workflow with one call to history and a bit of editing to clean up the output and save it as a shell script.

Your pipeline: Creating a script

Your supervisor insisted that all your analytics must be reproducible. The easiest way to capture all the steps is in a script.

First we return to your project directory:

$ cd ../../north-pacific-gyre/You create a file using nano …

$ nano do-stats.sh…which contains the following:

# Calculate stats for data files.

for datafile in "$@"

do

echo $datafile

bash goostats.sh $datafile stats-$datafile

doneYou save this in a file called do-stats.sh so that you can now re-do the first stage of your analysis by typing:

$ bash do-stats.sh NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txtYou can also do this:

$ bash do-stats.sh NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt | wc -lso that the output is just the number of files processed rather than the names of the files that were processed.

One thing to note about your script is that it lets the person running it decide what files to process. You could have written it as:

# Calculate stats for Site A and Site B data files.

for datafile in NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt

do

echo $datafile

bash goostats.sh $datafile stats-$datafile

doneThe advantage is that this always selects the right files: you doesn’t have to remember to exclude the ‘Z’ files. The disadvantage is that it always selects just those files — you can’t run it on all files (including the ‘Z’ files), or on the ‘G’ or ‘H’ files your colleagues in Antarctica are producing, without editing the script. If you wanted to be more adventurous, you could modify your script to check for command-line arguments, and use NENE*A.txt NENE*B.txt if none were provided. Of course, this introduces another tradeoff between flexibility and complexity.

Save commands in files (usually called shell scripts) for re-use.

bash [filename]runs the commands saved in a file.$@refers to all of a shell script’s command-line arguments.$1,$2, etc., refer to the first command-line argument, the second command-line argument, etc.Place variables in quotes if the values might have spaces in them.

Letting users decide what files to process is more flexible and more consistent with built-in Unix commands.